On a quiet part of New York’s Madison Avenue is the house and library of financier J.P. Morgan. The library, now a museum, has over 350,000 objects. To celebrate its 100th anniversary, the museum has a robust and intricate exhibition dedicated to Morgan’s librarian, Bella da Costa Greene.

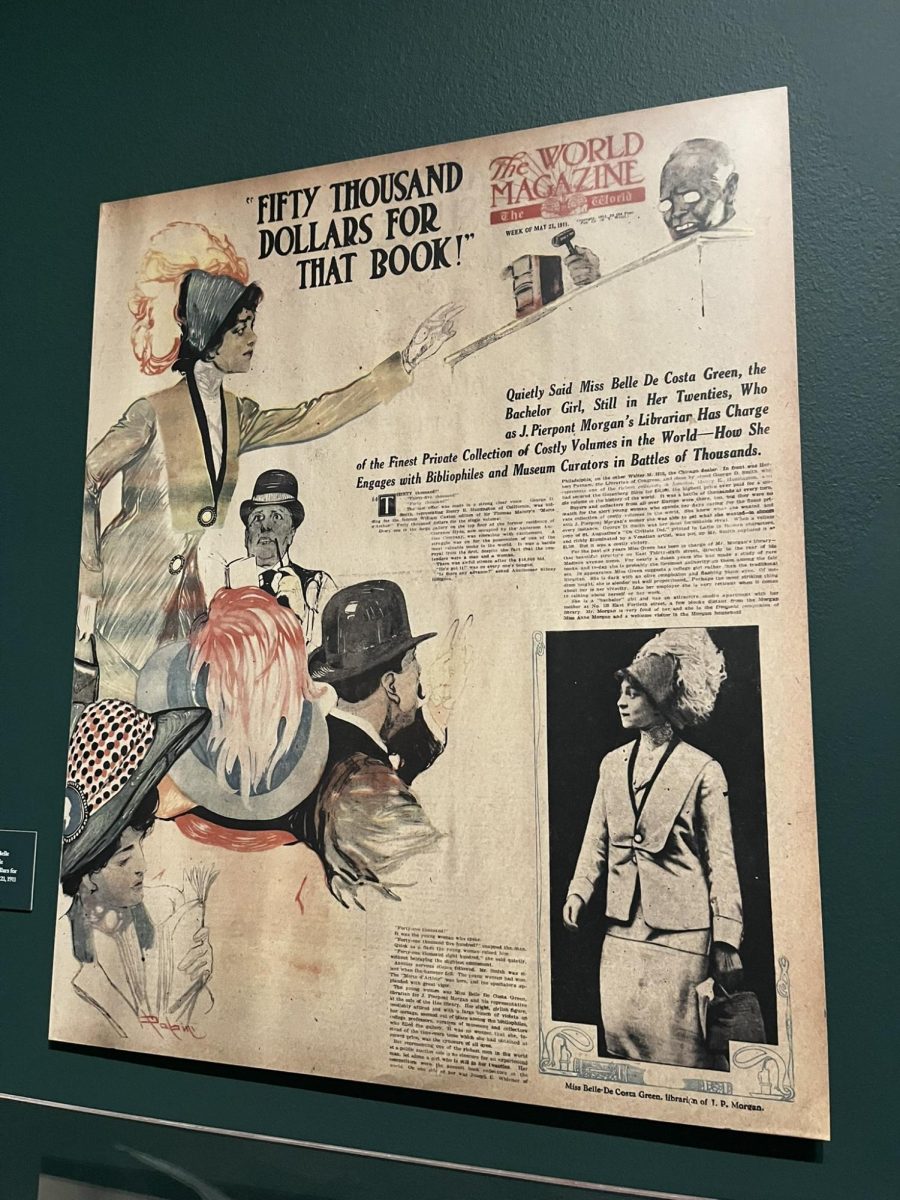

Belle da Costa Greene became a well-known librarian with astonishing media coverage during her career in the early-mid 1900s. She dedicated much of her life to purchasing and collecting illuminated manuscripts, Renaissance artwork, and other pieces with historical and artistic significance. One of her peak feats was working with the Morgan family, who at their peak owned about 80 million dollars— about 2.5 billion dollars adjusted for today’s inflation.

However, her story begins not in New York City but in Washington, D.C., near the affluent Georgetown neighborhood. Born to African American parents on November 26, 1879, Belle Greene passed as White for most of her life, claiming Portuguese ancestry. Belle Greene’s observable tenacity was fostered by her family’s success and education. Her father, Richard Theodore Greener, was the first Black graduate of Harvard University, and her mother, Genevieve Ida Fleet Greener, hailed from a prestigious Washington, D.C. family. Nevertheless, her parents were still free Black people amidst the racial turbulence of Jim Crow. The two separated when Belle Greene was young and thus began her ascent into Northern, white circles.

Living with her mother and siblings, Belle Greene attended preparatory school in Connecticut and received a fine upbringing that is somewhat unclear— Greene destroyed most of her personal writings before she died in 1950. Around 1902, Greene found employment in none other than Princeton University. It was a wonderful place for Greene to seek employment, even though the institution had been slow to remove the prejudices of slavery from its campus— a fact the Morgan Library highlights in the exhibit, as it is pertinent to the lived experiences and anxieties Belle Greene possibly had. During her time as a library student and worker, she befriended Junius Spencer Morgan, the nephew of J.P. Morgan.

In 1905, Greene became Junius’ overwhelmingly qualified assistant. She reached the ranks of J.P. Morgan’s private librarian, where she gained much success. Librarianship is a subtle, disciplined field, one that Greene knew she had an interest in ever since she entered preparatory schooling. She had not only an interest in librarianship but a talent. Documenting, appraising, discerning, and cataloging pieces are just a few of the skills she used as a personal librarian.

Belle Greene began to experience the world in ways unprecedented for a woman of color in her time. She traveled tremendously and began inserting herself into aristocratic circles, all in the name of librarianship and collectorship. She was shrewd in finding and bidding on the best pieces to add to the Morgan collection. She especially enjoyed finding medieval illuminated manuscripts (jewel-encrusted Bibles with gilt edges). She was quite perceptive, even learning how to uncover forgeries. In 1930, she reviewed a “suspicious” artwork for the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which was discovered to be forged by the “Spanish Forger.”

Though Greene worked tireless, long hours, she still had a personal life— one that was decidedly more exciting (and torrid?) than a stereotypical librarian. She was well known for her stylish outfits, wittily remarking, “Just because I’m a librarian, doesn’t mean that I have to dress like one.” She wore wide-brimmed, feather-plumed hats, furs, and dainty dresses. Effectively, she was brainy, attractive, and confident, which drew in men. In 1909, she wrote to her friend Bernard Berenson, the influential art historian, that she was “busily engaged hunting up particulars of a certain book & half the Library was on my desk.” Sharing a special sort of intimate relationship, they were not only admirers but also intellectuals— Greene’s librarian livelihood seemed to consume all areas of her life.

The elder Morgan died in 1913, but Belle Greene continued her preservationist and librarian role. She became the official director of the Pierpont Morgan Library, retiring in 1948. It is difficult to fully grasp the extent of her abilities. Much of her work was rediscovered and celebrated, thanks to archivists, librarians, and writers who worked tirelessly to keep Belle Greene’s history alive. Greene herself kept most of her personal life secret, never even marrying. She was utterly dedicated to her work and made impressive advances in White society. She sacrificed the truth of her racial identity but plunged into her other identity as a talented and bright librarian and woman. Today, in the West Wing of the Morgan Library still stands her large, imposing desk and card catologue where she kept track of some of the world’s most impressive artifacts.

Bibliography

https://www.themorgan.org/belle-greene

https://blogs.loc.gov/headlinesandheroes/2022/02/belle-de-costa-greene/

https://slavery.princeton.edu/stories/princeton-and-slavery-holding-the-center

https://www.themorgan.org/belle-greene/letters