Club members are complacent.

What do I mean by that?

Clubs and other school-sponsored extra-curricular organizations are complacent. They are a perfunctory staple of academic institutions— language clubs, special interest organizations, leadership groups, etc.— whose credibility falters. When my parents grew up during the 70s, chronic clubbers were unicorns. Today, teens are expected to actively participate in their communities, less as dependents than as radical humanitarians. We are told: “we are the future,” “the future is now,” and we must “be the change” before the future expires. Live while you can. Life is fleeting. Time is fleeting. Use it wisely… There are seemingly endless visionaries, and modern teens are painfully aware of the implications.

Said implications are as follows:

- Society needs fixing.

- People are morally obliged to better society.

- The work of societal improvement is perpetual.

Let’s begin with my first claim— society needs fixing. History textbooks tend to argue democracy exists because people want an active role in amending flawed systems, especially when the flaws affect them. For example, the abolitionists fought for the legal liberation of slaves and triumphed with the 13th Amendment’s ratification; America was identified as flawed and subsequently fixed for the better. From a religious point of view, Catholics proclaim their sins, a hallmark of imperfection. If people did not sin, they would not repent. Because they do, there must be something that can be improved. The same can be generalized to society; a community of sinners (essentially, normal people) is morally deficient. Since morality can be improved, it’s expected that the increased net good of this community is a virtuous goal for the sinners to maintain. This is, of course, assuming that the people acknowledge their faults.

As for my second claim, once again, consider the community of sinners, sinners of which can be almost anyone in the world. Maybe this community is that of a private Catholic girl’s school. Here, the students and faculty are taught by guest speakers, posters in the hallways, and each other that they can become better people through practice. Moreover, they are encouraged to spread their ministry of kindness and charity to connections beyond the community. Volunteering, hosting bake sales, and giving of themselves might be common efforts to spread goodness. In any case, inherently imperfect people take it upon themselves to share what goodness they owe to improve the quality of life (or morality) in others.

My final claim can be specified further via the Academy of Saint Elizabeth. Girls who attend our institution are educated per Catholic Social Teaching, a concept founded on the Bible, a work of sacred literature millennia old. It is assumed that its principles will proceed for millennia to come— well beyond the lifespan of one person. Therefore, every student at St. E’s who practices goodness contributes to a history of like-minded individuals. We stand on the work of every principal, teacher, custodian, parent, and student that came before. On the other hand, there will be countless others to stand on our moral foundation. Like a rock, the parent material continues to grow and diversify with time. Hypothetically, this could go on forever.

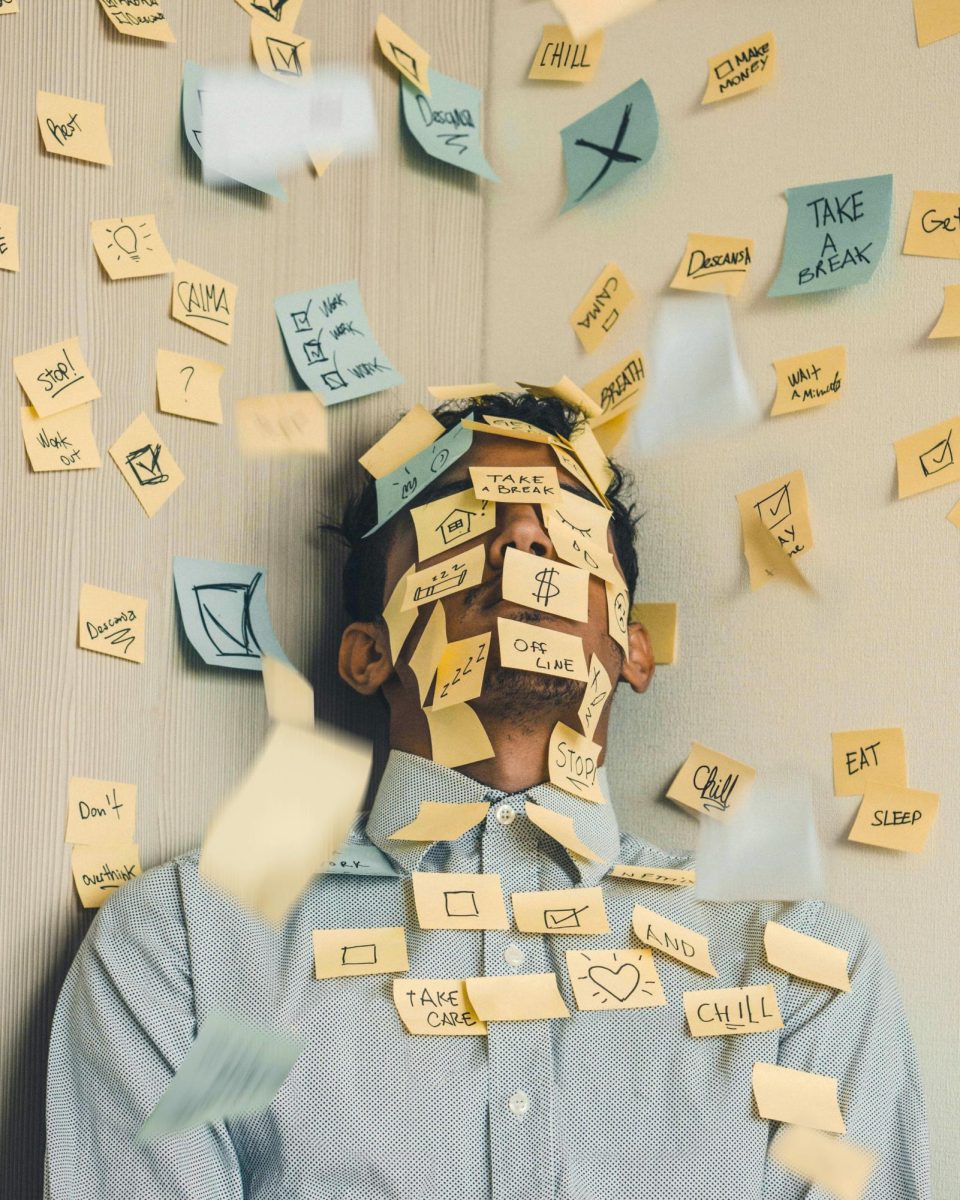

Especially for teens such as myself, considering perpetuity and our role often results in existential dread. It’s an amazing feeling, the fear for your mortal soul. Moreover, our mortality is frail. After years of studying history in school, the thinkers and their words are cemented in a common psyche. George Washington, for example, is a household name. Not only is he a name, but Washington is a symbol for and a synecdoche of America: his profile is on our legal tender. So, what? In learning about the greats, we are asked to compare ourselves to them.

Take another example: Jesus. To much of the world, Jesus Christ is the embodiment of goodness, and he is the goal. Jesus, mind you, is believed to have saved humanity in his 30s. Perhaps Jesus is an exception because He isn’t entirely human, but you start to see my point.

In more recent times, we can consider outstanding figures like Greta Thunberg and Malala Yousafzai. They are alive, they are young, and they are devoting their lives to helping the human race. Is that not the ideal? Even better, they are normal people, like you or me. They are normal, imperfect, sinning people. They are only a fraction of a genetic code away from anyone else. If they made it, then you and I could too be on the next page of the history books.

This is where the problem lies. Nowadays, people are taught of their potential to join the incredibles’. Realistically, though, not everyone is destined to be remembered. In other words, most of us will be forgotten. Most people will not actively make a dent in fixing society. Most of us will only go as far as to note that it is broken. But most people have neither the humility nor the courage to admit that.

If you maintain any hint of an ego, time passing without you can become a paralyzing fear. We’ve all been alive for X number of years and done Y to change the world, but is Y enough? It’s easy to define yourself by the changes you do or do not instigate or support. It’s like, democracy and the media give you an almost universal platform, and you haven’t fully taken advantage of that resource. You haven’t as effectively promoted your agenda of goodness as others. And maybe that’s alright with you. You accept that not everyone is George Washington or Jesus of Nazareth, Greta Thunberg or Malala Yousafzai. And yet, democracy and the media demand you make your mark. What do you do?

For kids, one of the most accessible methods of tackling the dread is by joining clubs born of extrinsic motivators. I and likely others fear that people now assume titles— from “President” to “member—” to prove their character; if your associated organization has positive connotations, you adopt some of that reputation. In this, we slouch through vague or overpromising agendas and skirt past the minimum meetings per season to legitimize an operation founded on something other than its toted mission statement, if it has one.

The state of clubs echoes the state of youth culture; children are forced into positions they cannot satisfy. Whatever the reason, be it clout-chasing, resumé-building, convenience, self-gratification, power, or desperation, kids are flocking to extra-curriculars. It’s as though everyone wants to be a leader when nobody knows how.

This is not a matter of whether or not people deserve to pursue their interests— encouraging youth involvement in different disciplines probably bolsters a well-rounded worldview— nor is this a matter of competence. In my experience, even “underqualified” passionate people can inspire improvement in themselves and commitment in others. Students should ideally be able to try whatever they want in a safe environment among peers (and usually moderators). Sometimes, moreover, club ventures fail— joining or founding a club should not marry you to it. It is the nature of some organizations to fall out of favor, and we should not preserve them for tradition alone. So, what I fear is not time, but the consequences of limited foresight. If a club leader truly loves their vocation, they will advocate for and promote its perpetuity, with the organization’s future always in mind: a solid club should not dissolve when its leader passes the baton if interest remains. If interest is not intrinsic, this explains today’s predicament: we don’t care.

We don’t care about our causes so much as our affectations of “fill-in-the-blank.” Clubs remind me of how people will repost something or other about something or other instead of more actively contributing to the conversation. Progress— personal and societal— is not generated by a peanut gallery. But in the name of robust offerings and precocious maturity, we market ourselves and our interests to no end, even through clubs.

This is not to say that all clubbers are misguided. At the Academy, for example, there are some students and faculty who compose a palpable and ever-beating heart for extra-curriculars. Unfortunately, they alone are insufficient to support a school, just as scant individuals struggle to move greater social reforms. I look to the future and see clubs and equivalents being mentioned only in passing as an almost tragic report of what results from excess pressure on children.

Ultimately, club members are complacent, but we don’t have to be. My question to readers, therefore, is what are you going to do about it?