Education depends on self-study. However, if your study methods are ineffective, the time and effort you devote to learning might be fruitless. If you spend hours reviewing without getting the results you’d like, chances are it’s worth inspecting your study habits themselves. This article will examine productive time-management tricks, note-taking tips, and other hacks.

Let’s start with time management. Though there is no set cure-all for procrastination, we can make work more manageable in some ways.

- The Pomodoro technique, not to be confused with the tomato, involves time scheduling. Many will try and fail to work uninterrupted hours, “cramming” as one might call it. After some time of concerted effort, the exhausted brain begs for distraction. Sometimes this decompression period overtakes the allotted study session. The Pomodoro technique suggests dividing time into 30-minute blocks to combat study fatigue. The first 25 minutes are for work, and the remaining five are devoted to play. Play may be time for a light snack, stretching, or texting friends. Then it’s back to work for another 25 minutes, and so on.

- The 5-Minute Rule is simple: if it takes less than 5 minutes, do it now. Small tasks like replying to emails or asking a teacher a question can feasibly be accomplished in less than 5 minutes, but it can be easy to put these small tasks off for days if not weeks. Over time, these forgotten 5-minute tasks amalgamate to become more urgent, stressful, and time-consuming. The solution? Get them out of the way when you have the time. The dopamine rush will encourage you to keep up the good work on more involved to-do’s.

- Counting down from a number– any small number will do– distracts you from your distraction. In essence, your brain becomes so focused on counting that it will do whatever you want when it hits “zero”. Applications for this range from stepping out of a shower (5, 4, 3, 2, 1, turn the water off), to getting out of bed (3, 2, 1, up and at ’em!), to closing an app, or to opening a textbook. Sometimes it is that intuitive. I encourage you to try it once and experience the magic of using your brain to your advantage.

We’ve reviewed three ways to tackle time. Next up, let’s find out some ways to take notes.

- AP Psychology textbooks love the SQ3R method, and so do its students. SQ3R stands for survey, question, read, recite, and review. These are the steps and sequences in which psychologists and educators suggest learning information. Consider you’re assigned to read a section in your textbook for homework. Using the SQ3R method, you would first survey the section– flip through its length, taking note of illustrations, headings, etc. You’d then ask questions about what you’ve just seen: What do you know? What don’t you know? What would you like to learn? Next, you read the section, take notes (thereby reciting the information), and review incrementally to keep the information locked in.

- Handwritten notes are generally considered better for later recall than typed ones. Some psychologists argue that notes of any form will do, but handwritten have worked for centuries and continue to be popular today. When you’re handwriting your notes, be they re-written (as opposed to re-copied) from class or fresh from the textbook, remember that they are your notes; write that you may understand. Keep notes legible and organized, and you’re ahead of the game.

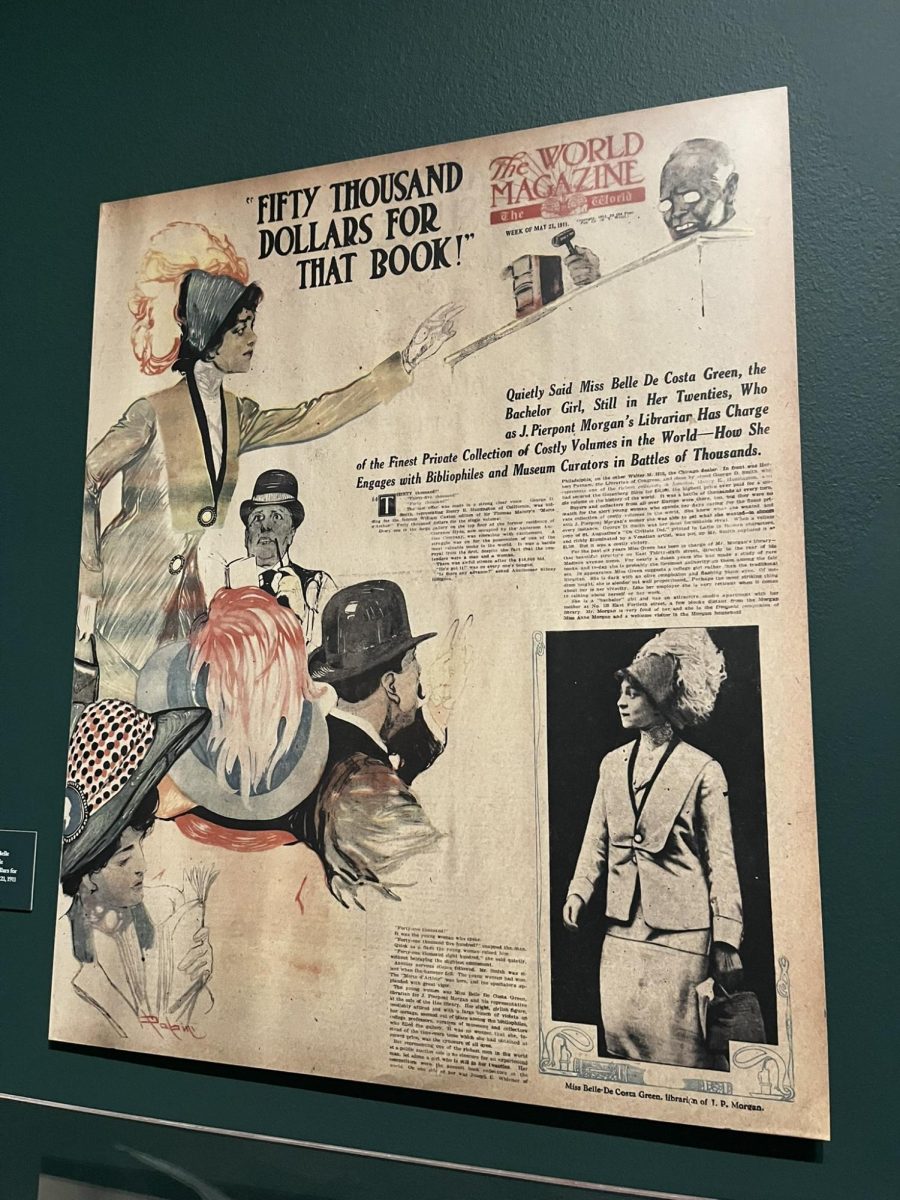

- THIEVES is a shrewd acronym that translates to title, headings, introduction, every first sentence in a paragraph, visuals and vocabulary, end-of-chapter questions, and summary. In this, it bears similarity to SQ3R. However, where SQ3R details how to digest and review, THIEVES highlights the “survey”, or previewing of a work. This video is well-loved by almost 10 million viewers and explains in more detail.

Note-taking methods are out of the way, which means it’s time to review some ways to review!

- Einstein famously said, “If you can’t explain it to a six-year-old, you don’t understand it yourself.” Taking one from the empirical master, teaching others solidifies information in your mind. Tell your friends, parents, or nearby inanimate objects your educational exploits at length. Trying to teach others further identifies areas of confusion; if you find yourself tripping on facts or doubting your knowledge, you know where to review.

- Mnemonic devices employ acronyms or phrases, such as THIEVES, to help people remember otherwise complicated sequences. For example, Every Good Boy Does Fine is a common mnemonic device to help music theory students remember notes in the treble clef (EGBDF). PNK (pronounced “pink”) represents phosphorous, nitrogen, and potassium, three important nutrients for plant growth. King Henry Died By Drinking Chocolate Milk is perfect for metric conversions, SohCahToa for trigonometric functions… the list goes on.

- Flashcards involve writing a term on one side of a note card and the definition on the reverse. They are quick to make, easy to carry, and effectively gamify learning to make even long lists of vocabulary manageable.

With that, a cursory glance at how to study is complete. Everyone is different: though the learning types have been debunked for years, it remains true that every student is an individual. What works for some may not work well for others. So, above all, have patience with yourself as you define your favorite study methods. And remember, it’s more important to understand the information than to get the highest score on an assessment.

To quote the Bard, “No profit grows where is no pleasure ta’en. In brief, sir, study what you most affect.”

Learn on, have fun, and do your best!